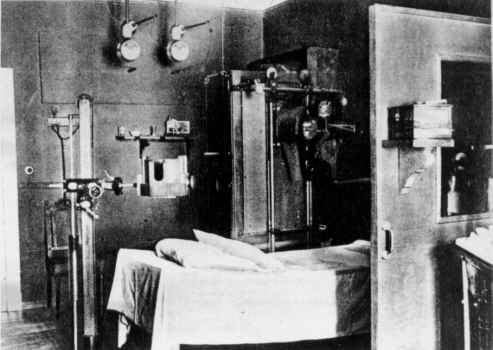

THE CLINICAL SPACE

Magnus Hirschfeld studied medicine and literature. He trained and practised as a medical doctor and regularly saw patients. His Institute included clinical facilities where he and his colleagues could meet, examine and interview patients. Many of these patients were lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and/or intersex.

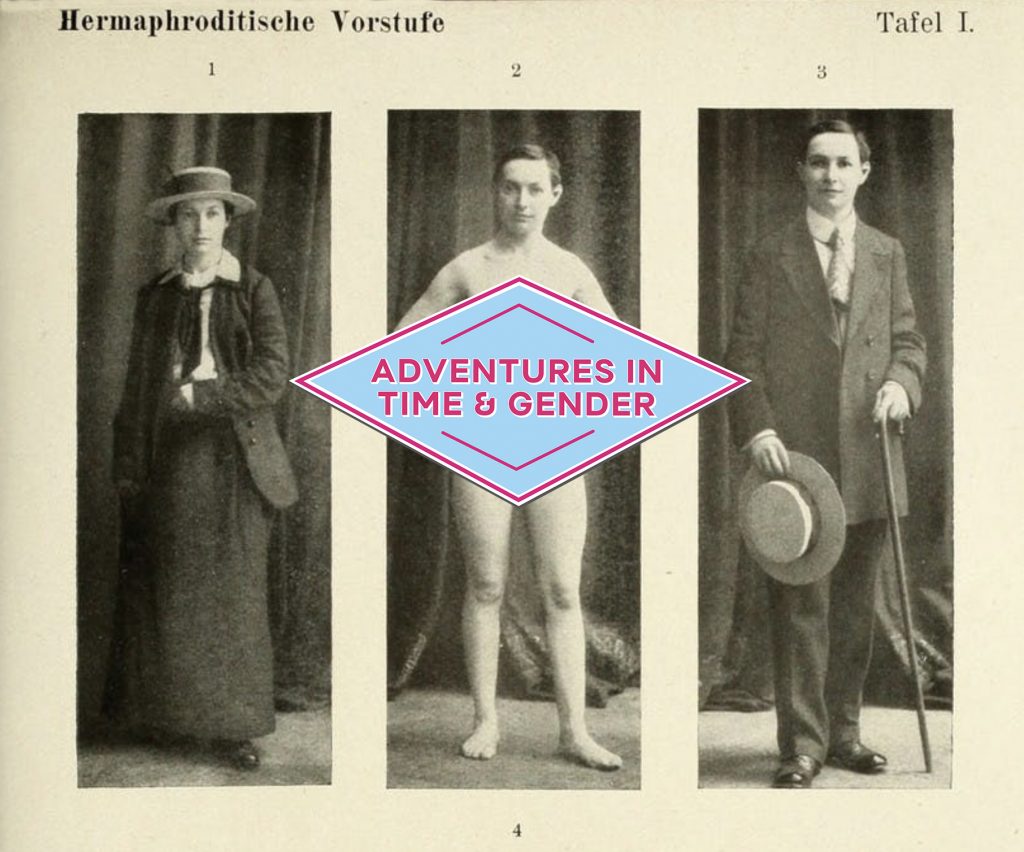

Hirschfeld believed that sexual and gender diversity was grounded in biology and therefore natural. He used the term “Sexuelle Zwischenstufen” (Sexual Intermediaries) to describe various gendered and sexual possibilities. To prove that gender and sexuality could be experienced and expressed in diverse ways, Hirschfeld collected information from his patients in the form of personal narratives, photographs and clinical observations. Without the input of his patients – without their voices and experiences – Hirschfeld would not have been able to become one of the most famous sexologists of his time.

“There are more [gendered and sexual] emotions and phenomena than words. […] We have to treat sexual intermediaries as widespread and important natural phenomena.”

Magnus Hirschfeld, Die Transvestiten: Eine Untersuchung Über den Erotischen Verkleidungstrieb, 1910

Hirschfeld used his scholarship for good: he fought vehemently to change German law, which criminalised male homosexuality under paragraph 175. He was publicly ridiculed, attacked and assaulted because of his activism and because his own homosexuality was an open secret. The fact that he was Jewish was also used to slander him.

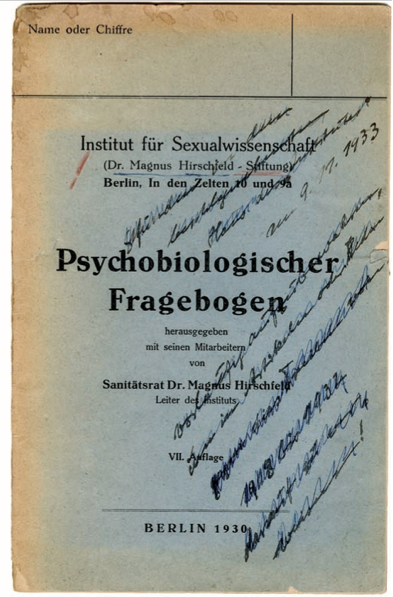

Collection Beat Frischknecht.

To prove that homosexuality was natural and common, Hirschfeld wanted to develop a scientific method to diagnose homosexuality. He devised a “psycho-biological questionnaire” that he asked patients to answer to find out whether they were gay or lesbian. The questionnaire was very long and included questions about a person’s family history, childhood, body, character and erotic desires and sexual experiences. Hirschfeld also wanted to know, for instance, whether a person could whistle and how firmly they shook hands. The questionnaire affirmed people’s identities, but it also created and reinforced scripts and stereotypes that many queer people still struggle with today.

Hirschfeld developed a new language to describe trans identities, coining the term ‘transvestite’ in 1910. He helped many trans patients who came to see him at the Institute to transition socially. In 1909, he urged Berlin police officials to issue so-called “Transvestitenpässe” (transvestite passes) after seeking his medical opinion. These passes enabled a person to wear the clothes they wanted to wear and live in the gender role with which they identified without attracting police attention. The picture shows the pass used by Gert Katter, a trans man, who was one of Hirschfeld’s patients.

In the 1920s and early 1930s, the Institute would play an important role in supporting trans people who wanted to transition medically. Hirschfeld met Lili Elbe at the Institute in 1930 and supervised her treatment. He helped her to have the surgeries she wanted, which were carried out in the practice of one of Hirschfeld’s colleagues in Berlin and later on in Dresden.

While Hirschfeld helped trans people and affirmed their identities, he also drew on their lives and experiences to further his own career and secure his authority as a medical doctor. Hirschfeld classified his patients and took photographs of them, which he published. For instance, the photographs of trans man “Amandus B.” (a pseudonym) in Hirschfeld’s medical textbook Sexualpathologie (1920) objectify and medicalise trans bodies and raise challenging questions about consent.

The Institute and Hirschfeld’s activism were controversial. Whether he and other members of the Institute produced ‘real’ science was widely debated among other scientists and doctors. An anonymous report from 1920 (possibly co-authored by one of Hirschfeld’s chief rivals, the doctor Albert Moll) harshly criticised the Institute.

The Institute is “not really considerably scientific; it serves 1) to generate income; 2) to exploit people; 3) to seduce young people on the cusp of sexual development who would otherwise develop normally; 4) to match-make.”

Anonymous Report, 1920